article> Science

Women in AI: novel field, same old biases?

Nathalie Smuha, a KU Leuven researcher on the 2021 list of the 100 brilliant women in AI Ethics, explains the issues currently facing the ethical use of Artificial Intelligence.

by Sara Blanco

Contributing Writer

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the field devoted to building artificial creatures which aim to supply and/or complement human performance in certain contexts. In other words, we could say that AI is a discipline which aims to build rational agents. Then, the goal is to develop systems capable of learning and making decisions. This comes with an ethical component attached to it, that needs to be taken into account. Initiatives such as the High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence by the European Commission or the Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems by the IEEE are making progress in this regard.

Ethics of AI is a wide branch of ethics which concerns a variety of topics, from human-AI relationships to which values (if any) should be encoded in the algorithms in order to develop morally responsible AI. As we have said, the goal of AI is to develop systems capable of decision making. This is already possible, since in the market we can find AIs able to provide medical diagnosis, sort CVs, decide whether to grant someone a loan or not, etc. In these examples is particularly clear how AI is entangled with society, and therefore its decisions can play a significant role in our lives. Because of this, developing ethical AI is crucial; we do not only want AI which is able to make decisions, but morally responsible decisions. This is a complicated matter, since moral responsibility is controversial even when it only concerns human agents. Incorporating new technology that we have not completely figured out yet in complicated philosophical dilemmas is challenging. However, AI is not going anywhere, and since the conundrum is unavoidable, it is urgent to shed some light on it.

One of the ethical challenges that AI faces is bias. A good example of AI bias can be found in Amazon's recruiting system. They worked for years on an AI capable of sorting job applications and automatically detecting the best ones. It was designed to do this in an objective way. However, because it was trained with a database of resumes submitted over a 10 year period, the AI taught itself that male candidates were preferred. This case highlights not only how important is to understand how algorithmic decisions are made, but also the current position of women in the field. The gender gap is still a reality across nearly every discipline, but the situation in areas such as engineering and exact sciences is even more striking. Only 22% of the jobs in AI are held by women, according to recent research by the World Economic Forum and LinkedIn. In KU Leuven in particular, if we look at the data from Engineering Sciences, only 371 women were enrolled in this bachelor, in contrast to 1.204 men (almost three times more).

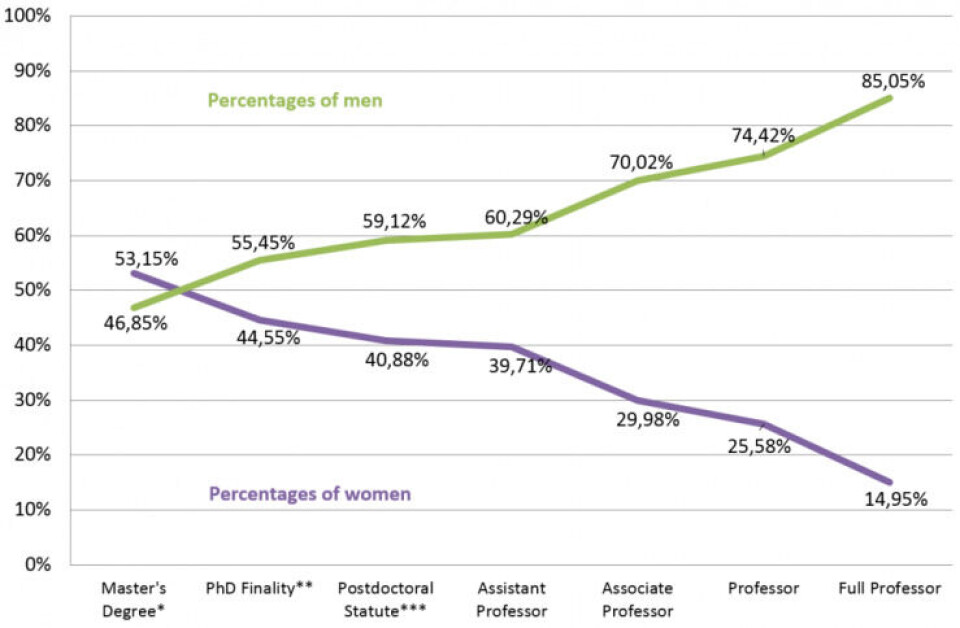

Scissors diagram showing the percentage of men vs women at different levels of the academic hierarchy in 2016 from the Quarterly Report of the KU Leuven HR Department (Editing: Tom Bekers).

As we can see in the scissors diagram, the gap increases the higher the position in academia (even though women generally outperform men’s marks in exact sciences).

Just as it happens with algorithms, the world tends to keep repeating the patterns that are already present. The current lack of women in AI perpetuates the situation, and because of it, initiatives as the annual list of 100 brilliant women in AI Ethics are necessary to give visualization to the women who are making great achievements in the field and who could inspire others to follow the same path. Their list for 2021 includes KU Leuven researcher Nathalie Smuha. With a background in philosophy and law, Smuha works at the Faculty of Law and is also a member of the Working Group on Philosophy of Technology (WGPT), focusing on ethical and legal matters concerning AI. She coordinated the High-Level Expert Group on AI at the European Commission, which has released Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, addressed to AI practitioners and AI Policy and Investment Recommendations, addressed to the European Commission and Member States. At the moment, she has her eye on the governance mechanisms needed for guaranteeing trustworthy AI, and the risks of using AI in certain contexts. We had the pleasure to ask her some questions about her work and views on some AI ethics hot topics.

Sara Blanco (SB): “I have read that you coordinated the High-Level Expert Group on AI at the EC, which recently released ethic guidelines for trustworthy AI. Such guidelines are an important step towards international agreement on where to draw the line in the use of AI and which criteria should be met in order to be morally responsible. However, these guidelines are non-binding recommendations. Do you think that stronger legislation is or will be needed in the future in order to guarantee that the private sector respects a common moral ground?”

Nathalie Smuha (NS): “The Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, drafted by the Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on AI, were a useful starting point to map the ethical issues arising from the development and use of AI and to look for a consensus of multiple stakeholders (academia, civil society, industry) on what those issues are. Moreover, the Assessment List at the end of the Guidelines also attempts to start operationalizing those guidelines, so that they can be actually implemented in practice. However, there are certain ethical risks that cannot sufficiently be addressed through non-binding guidelines, but where binding legislation is needed. Certain AI-applications can have an impact which is too detrimental to individuals or even society at large. This is why a number of regulators (such as the European Commission, but also the Council of Europe) are considering the adoption of new binding legislation to ensure that AI is used in a manner that aligns with ethical values and that respects human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Interestingly, the fact that binding regulation is needed, is increasingly also acknowledged by the private sector. Companies like Microsoft and IBM have for instance asked for a legally binding framework for the use of facial recognition technology that can provide them with legal certainty as regards how and when it can be used. Moreover, legislation can ensure that there is no ‘race to the bottom’: by establishing a legal level playing field of minimum rules that companies must respect, they can no longer try to prioritize profit over ethics. Of course, it is important to make sure that whichever new regulation is adopted will be tailored to the specific problems raised by AI, so that it is not overly rigid and does not hamper socially beneficial innovation. This is a careful balancing exercise that will need to be made by regulators, for which it is useful to consult with multiple stakeholders.”

SB: “AI is a wide concept, an umbrella term. However, it is often said that it needs to be regulated, as a whole. Do we need specific laws to regulate AI? Why can’t we use the current legislation that applies to other kinds of software?”

NS: “Absolutely: AI is an umbrella term which covers many different types of technologies and techniques that are considered ‘intelligent’. In addition to the variety of AI techniques, there are also numerous AI applications, from speech and facial recognition systems to recommender systems based on people’s profiles (recommending anything from the books you should buy or songs you should listen to, to the social media content that you should be interested to see). Moreover, even if similar applications can be used for different purposes or contexts, the sector or application-domain in which the AI system is used can have a major ethical relevance too.”

“There is a difference between an AI system that erroneously recommends you a song you don’t like, and an AI system that erroneously recommends a medical treatment for a potential life-threatening disease.”

“Therefore, regulators are currently examining the possibility to regulate only so-called “high risk” AI-applications. Of course, the major difficulty consists of identifying what constitutes a high risk. There will be cases where it is immediately evident that the non-responsible use of an AI system can have a negative impact on people. Think of an AI system used by the government to allocate welfare benefits, or an AI system used by the police to identify potential suspects, or an AI system used by employers to sift through CVs, or by a bank to grant a loan. But there are also AI applications where it will be less clear if / to which extent there can be a high risk for individuals, and hence whether it should fall under the scope of a new AI regulation. So it would be important to develop risk assessments (for instance human rights impact assessments) in order to determine the risk level in the first place.”

“The reason why “high risk” AI applications require new regulation, is because the currently applicable rules have some legal gaps. Both at national and at European level, there exists already some regulation that also applies to the use of AI (such as, for instance, the European General Data Protection Regulation, which provides safeguards whenever citizens’ personal data are used, regardless of whether this data is processed by a basic computer program or by an advanced AI system). However, existing regulation does not provide comprehensive protection against the risks raised specifically by AI. These risks are not yet accounted for in law because they are not necessarily present with other types of software. Think of the fact that, for some AI systems, even the developers don’t know how the system arrives at a certain decision (the black-box problem, or the lack of transparency). Yet the more we delegate decisions and hence authority to AI systems – especially when these decisions can significantly affect people’s lives – the more we need to ensure that these systems operate in a legal, ethical and robust manner.”

SB: “Ethical guidelines often demand transparent AI rather than black boxes. What do you understand by transparency? Should the whole algorithm of an AI be available to the public? What if this creates a conflict of interest with the developers, which may not be willing to make their algorithms public due to competence reasons.”

NS: “The requirement of transparency can cover many different elements. One should, however, consider the reasons behind the need for transparency, because it is on that basis that you can assess which element is needed. For instance, if I’m an individual who is subjected to an AI system that decides whether or not I get a loan, I don’t need to have the source code of the algorithm. I need to get an explanation of the process of the decision-making and the factors that were relevant to make the decision, so that – if need be – I have the necessary information to challenge or contest the decision and / or the process. Moreover, whenever this is unclear, I should be informed of the fact that I am interacting with an AI-system and not with a human being (for instance in the context of AI-enabled chatbots).”

“For AI systems that can have a significant impact on individuals or society, it would be good that the system is traceable."

“It may not always be possible to understand how a decision comes about (due to the so-called black box problem), but AI developers can still document the data sets and processes that were used to arrive at a decision (which data was selected? how was it gathered and labelled? which algorithm was used?). If this information is not documented somewhere, it cannot be verified ex post whether a law was breached or inaccuracies slipped into the process. This doesn’t mean that everyone should necessarily have access to this type of information. Indeed, sometimes intellectual property rights or trade secrets apply. However, public authorities should still be able to verify whether the law was respected. And this information could also be provided to trusted third parties to carry out independent audits of the system and confirm conformity with certain rules.”

“So, in short, transparency requirements are ideally tailored to the specific situation or context, and to the specific actor (e.g. an individual subjected to the AI system, an expert, a public authority, an auditor).”

AI ethics ensures that the field evolves towards a moral direction, rather than focusing on economic benefit only. When talking about AI, the consequences of this new technology often seem unpersonal. However, there are always people behind the systems: developers, operators, stake holders, policy makers, etc. Responsibility needs to be taken for algorithmic decisions, and in order to shape the world in a constructive way, certain values must be considered. If we aim to live in a diverse society, we need to take initiative and make sure that every population group is taken into account when making decisions that affect social issues. In the case of AI, this means, among others, to ensure that we count with a diverse learning database. AI bias is often unintentional, and therefore only comes to our attention when there have already been negative consequences. However, even if such mistakes happen without malicious intentions, they are often the result of the technology being developed by a very homogeneous group of people. If most of the people who work on AI are white males, it makes sense that the technology focus on their needs and adapts to their circumstances. We can observe this on a variety of cases, from medical diagnosis tools which are significantly less successful on black patients to voice recognition systems which fail to understand women’s voices.

Quoting Ivana Bartoletti, co-founder of the Women Leading in AI Network,

“If the people working on artificial intelligence tools, products and services don’t resemble the society their inventions are supposed to transform, then that is not good Artificial Intelligence – and we shouldn’t have it. Increasing diversity in AI needs to move from just talk to actually doing something about it – and this is not just about coding, it is also about the boardrooms where the decisions on AI are being made.”

Ivana Bartoletti, Technical Director - Privacy at Deloitte

Initiatives like the list of 100 brilliant women in AI help to inspire more women to participate in the field, and companies to give equal opportunities. A field which affects everyone, should represent everyone. A more diverse market helps to fight against bias and to walk towards a more inclusive society. More can be found about the topic on the Women in AI website. For a broader perspective on both gender and ethnic bias, this talk by Joy Buolamwini will for sure also give you something to think about and further links to keep digging.

For more regular content

- Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thevoice.loko

- Check out our Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/thevoice.kuleuven/

- Listen to our podcasts on: https://www.mixcloud.com/The_Voice_KUL_Student_Radio

For submissions or applications

- Email us at thevoice@loko.be

- Or message us on Facebook