article> Opinion/Politics

Navigating allegations of Chinese espionage and interference in academia

Whether or not there should be genuine concerns over espionage and interference in academia from the Chinese government and how to respond to this is a complex topic with many sides to it

by Seyhan Kâhya and Marit Pepplinkhuizen

Contributing Writer & Opinion/Politics Section Editor

On the 2nd of November, Veto published in their international affairs section an article about the concerns of KU Leuven and the Belgian State Security Service (VSSE) over Chinese espionage in academia. This article was then shared on the Pangaea community - KU Leuven Facebook group, and in a short amount of time ‘the internet’ showed how fiercely debates can be held within the comments section of a post. The article received significant attention from members of the community with more than 130 replies by when the comments section was closed (an unusually high number when compared with other posts on the group). The discussion initially seemed centred around whether the article referred to valid and factual national security concerns, or whether it was a reflection of xenophobia against Chinese students. In other words, some people were concerned that this was “widespread, vaguely racist fear-mongering about China” as commented by one of the members of the community to which the author of the post responded: “Showing the facts and the duty to report it is not racism or discrimination.”

However, what could have been a constructive discussion over differing opinions quickly shifted to a series of personal attacks and insults targeted at the author of the post ranging from “funny mud pee” to an actual threat calling for torture and extermination at a place synonymous with Chinese concentration camps of the Uyghur minority group: “remove this article now or your family will be sent to East-Turkestan re-education camp”.

This comment in particular crossed a line, and the admins of the Facebook group saw themselves obliged to intervene. The Pangaea staff deleted the comment, as well as a few others, and turned off commenting altogether after a final statement from Pangaea KU Leuven reminding members of the group about how to properly conduct a discussion including a warning for anyone who does not follow the rules stating that their posts or comments could be deleted and they may even be removed from the group. “We welcome debate and discussions which take place in a respectful way. Some discussions get very heated and the tone of comments becomes ugly. We highly disapprove this kind of speech” said the Pangaea staff in the final comment. The heated debate made one thing clear though: that more information was needed from all sides of this issue.

In academia, whether or not to launch a new scientific project is often determined by two key factors: the impact of publications (or patents) that could result from the project and the amount of third-party funding available for the project. The latter makes it especially attractive to cooperate with academic institutions from China, due to their high purchasing power and willingness to fund, for instance, their academic staff working at European universities. Nevertheless, Chinese institutions are sometimes considered as a controversial partner due to heavily debated concerns over national security, as was reflected in the comments section of the post on the Pangaea community.

Unfortunately, the discourse is often rife with oversimplifications and stereotypes. In the following, we aim to contextualize the discourse, providing more clarity and facts for future debates.

China’s global influence

The People’s Republic of China frequently shines in the news due to its economic power, particularly because of an ambitious call to transform its economy from “the world’s factory” to “the world’s powerhouse in tech industries” with the Made in China 2025 programme, or by erecting hospitals in less than a fortnight to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Contrastingly, the Chinese government is also repeatedly under an unfavourable limelight by swinging the truncheon of repression in Hong Kong, and its persecution of Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority group. An additional item on the list of allegations is catching media attention: espionage.

When it comes to discussing Chinese espionage we can refer to Nicholas Eftimiades, a renowned scholar who has worked for decades on the topic. Looking beyond anecdotes, Mr. Eftimiades gathered and analyzed nearly 600 cases of Chinese espionage in the United States. He described that the Chinese agents involved in these cases are related to entities such as the governing Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Ministry of State Security (an intelligence organization) and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), among others. Yet, not every allegation leads to a conviction. When we asked about the number of convictions differing from the number of allegations, Mr. Eftimiades explained to The Voice that “it is an ongoing process. Many cases take years to litigate. In other cases the suspect is a fugitive. I list them all as pending until a final disposition is reached. I estimate 90 percent of cases end up in conviction.”

As for in Belgium, the Flemish newspaper Standaard reported that the provisions to the Belgian espionage law were created in the 1930s. Hence, allegations on espionage are litigated as invasion of privacy instead, for instance. Furthermore, litigations concerning espionage are held behind locked doors, for reasons of state security. Nevertheless, espionage by Chinese entities has been listed in the national security report 2019 by the VSSE as one of the three biggest national threats. And this threat is stated to reach beyond industrial espionage by also affecting academia. As a result, the VSSE has launched an awareness programme on the risks of academic espionage by Chinese agents related to research of dual-use systems, which encompass technologies that can be applied for both, civilian and military use - such as drones.

Entanglement of military and civil research at Chinese universities

In principle, one way of assessing whether research is used in a civil or military context would be to scrutinize the ties of the university to certain government ministries. This, however, is not easily possible in the case of China, as there is no clear cut between the categories of civilian and military. This requires further explanation, which can be found in the research of Elsa B. Kania, who is a scholar at Harvard University’s Department of Government, among other affiliations, and has a working proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. Her research examines Chinese military learning and innovation from a historical and comparative perspective, which is crucial to grasp in order to understand the military-civil entanglements, as described in her 2019 article published in The Strategy Bridge.

In 1978, two years after Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping, the then general secretary of the CCP, announced the ‘military-civilian integration’. A national strategy blurring the borders between the civilian and military realm aiming to diffuse military technologies to the civilian domain and therewith, strengthening the civilian economy. Over the course of the years, the CCP has nurtured the military-civilian kinship.

Then, at the 19th party congress in 2017, the current central committee of the CCP elevated the integration when secretary general of the CCP and president, Xi Jinping, announced a ‘military-civilian fusion’. The fusion defines a slogan to maximize the linkage between the two realms and govern the diffusion of civilian technology into defense research in key areas, such as artificial intelligence. This does not imply the militarization of every single university in China, but it is a detail worth considering in future assessments for academic co-operations.

The blurred borders between the civil and military sector complicates the allegiances of Chinese universities.

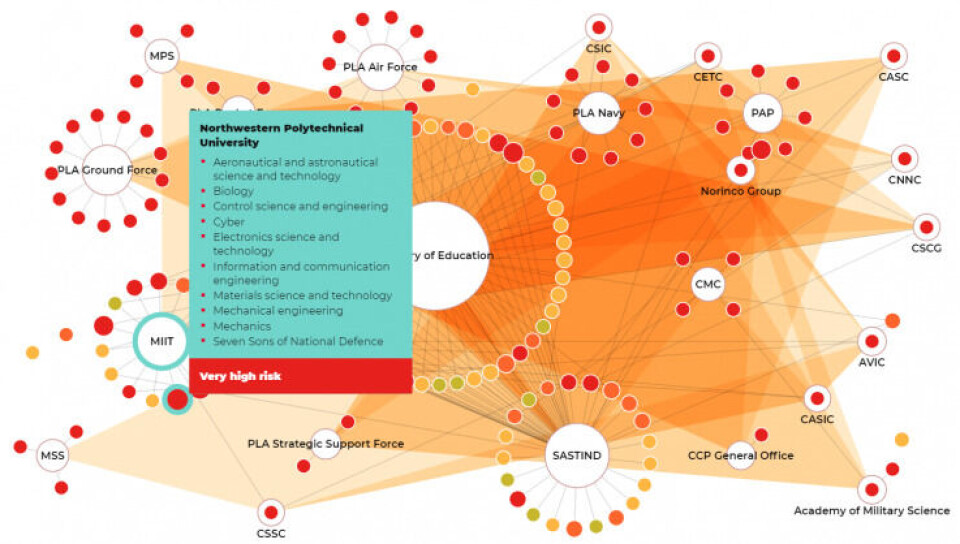

The question of whether a university has ties to the military should rather be asked in terms of the degree and extent to which a university is intertwined with research in military technologies. This is also how the VSSE assesses potential risks of espionage. The VSSE issues warnings on the risk of espionage using the China Defence Universities Tracker (unitracker) developed in 2019 by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. The tracker is a database enriched with information on aforementioned entanglement, on research laboratories designated for defence research, and listing economic misconduct and espionage amongst others.

Visualization of Chinese universities entangled with the Chinese military by the China Defence Universities Tracker (unitracker).

Despite these warnings, the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) has a long-standing cooperation with the Northwestern Polytechnical University (NPU) in Xi'an. NPU has its legacy in PLA’s Military Engineering Institute, among other institutes. Furthermore, NPU is part of MIIT’s ‘Seven Sons of National Defence’, a network of universities striving to research cutting edge defence technologies. Hence, technology developed at NPU could become a tool in the Chinese government’s repression tactics and violations of human rights, and is therefore listed as a ‘very high risk’ by unitracker.

The cooperation of VUB and NPU began in the early 1990s with the research group of the now emeritus Prof. Jan Cornelis. Prof. Cornelis is an electrical engineer with expertise in digital image and video processing, an attractive field for surveillance and useful for the development of facial recognition algorithms. However, this cooperation has been perceived as controversial in Belgium. Consequently, the Belgian magazine Knack asked Prof. Cornelis to comment over his field of research being used against Uyghurs in China and Prof. Cornelis replied “I am very sorry that technology is used for such applications. I don't approve of that. [...] I work with local scientists and hardly ever with the Chinese government.” Nevertheless, in 2015, Prof. Cornelis successfully championed the idea of opening a Confucius Institute at the VUB.

The Confucius Institutes: a cover up for Chinese interference?

Confucius Institutes are globally active organizations, promoting the study of Chinese language and culture. They organize events, such as for instance Chinese Tea Culture seminar or preparatory classes for the Chinese proficiency test Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK). Other countries have similar institutions, such as the Goethe-Institut promoting the study of German, or l’Alliance Française for French. Confucius Institutes usually partner with educational institutions between primary school and universities in the host country, and are funded by China. They are administered by the Chinese Ministry of Education, and count a remarkable number of 541 institutes since their launch in 2004. The Confucius Institutes are associated with the longer arm of China’s propaganda machinery exercising ‘soft power’. This is also related to President Xi’s call to ‘tell the China story well’, to show the richness and multidimensionality of China to an international audience. This, of course, means to tell the story according to China’s history as seen by the CCP.

Confucius Institutes have a bad reputation worldwide, being accused of brainwashing students, coercing universities into self-censorship, and threats of retracting funding. The US has designated Confucius Institutes as a foreign propaganda mission. In a press statement released in August of this year, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called them "an entity advancing Beijing's global propaganda and malign influence campaign" on classrooms and campuses in the US. However, these accusations came amid worsening relations between China and the US. On the other hand, according to Science Business, Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at Oxford University, stated that “There’s nothing that prompts any change of stance on China. This is all about the US maintaining its leadership. The idea that everyone is a spy in China is just a fantasy, reality TV gone mad.” In the same article, Dominic Sachsenmaier, who holds a chair professorship in “Modern China with a Special Emphasis on Global Historical Perspectives” at the University of Göttingen, is quoted arguing along the same lines.

“There can be instances where it might make sense to exclude international researchers from certain projects. But what we’ve seen in the US, for example, goes too far. I don’t think there’s any danger to labs from Chinese researchers, except in rare instances.”

Prof. Dr. Dominic Sachsenmaier, Professor of Chinese Studies at University of Göttingen

Furthermore, numerous incidents have been reported, where representatives of Confucius Institutes have vocalized their disappointment in the form of requests for censorship, when academics have published findings in opposition of the CCP’s writing of history. The global debate about Confucius Institutes reached its pinnacle in 2014 during a scientific conference of the European Association for Chinese Studies in Braga, Portugal. Upon arrival at the conference, Xu Lin, the director general and chief executive of the Confucius Institutes ordered her staff to remove pages of the conference booklet that were not on a par with the CCP. The pages included a testimony that the conference was sponsored by the Confucius China Studies Program and pages mentioning Taiwan. In a later BBC interview, when asked if the pages had been removed because they mentioned Taiwan, Ms. Xu changed her tone and rebuked the interviewer telling him that ‘Taiwan is a Chinese issue’, and that it is none of his business to interfere. She added that if she had known that he would ask this, she would have refused the interview. Needless to say, removing parts of a book for not complying with the CCP is a form of censorship against scientific principles. This incident was the tipping point to either terminate or not-renew contracts with the Confucius Institutes for numerous universities across Europe and North America.

Both Brussels universities, ULB and VUB, announced they would not renew expiring contracts with their residing Confucius Institutes in 2019. This decision came after the travel ban of Prof. Xinning Song, the head of the Confucius Institute at VUB, to the Schengen area. Prof. Xinning has been accused of academic espionage and recruitment for Chinese intelligence. Although he has won his first appeal based on procedural matters, the Belgian alien's office ('dienst vreemdelingenzaken') issued a second entry ban, according to the procedural rules. Hence, Prof. Xinning is banned from entering the Schengen area for 8 years, as was confirmed by Belgian officials. Veto reported in 2016, hat the KU Leuven decided to keep ‘a certain distance’ and not host a Confucius Institute. However, the same is not true about ‘Group T Academy’, an organization promoting internationalization at ‘Group T’. Here, the contract of the Confucius Institute is due to end in 2021, with only small chances of renewal.

Chinese Interference in Academia

Even when there is no solid proof of espionage or brainwashing, one thing that can be said with more certainty is that Chinese students and academics have been eager to partake in smearing campaigns of academics who have been critical of China. According to an article by The Guardian Ann-Marie Brady, a renowned China scholar from New-Zealand, who spent more than two decades analysing the Chinese communist party and exposing Chinese infiltration efforts, now faces the prospect of losing her job after writing a paper on academics who she alleges have links to Chinese universities. Moreover, Dr. Andreas Fulda, specialized in EU-China relations and author of The Struggle for Democracy in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong: Sharp Power and its Discontents, is facing threats and harassment after exposing the extent by which the CCP attempts to influence academic debates abroad.

In view of these allegations of interference, The Voice asked Prof. Nicolas Standaert, a trained historian and head of the sinology research unit at KU Leuven, if local scholars have received repercussions for their research, such as threats, not having their visas issued or having articles rejected. Prof. Standaert explained that “there is no case known to me, that our staff has experienced something as such” and added, after a short pause, “maybe because our field of research is not that delicate. It happened to international scholars that they did not receive their visa to enter China after publishing critical articles”. When asked about self-censoring, he mentioned that “there is a subtle pressure”, but this has not affected his academic track record. He also said jokingly that he has never been “invited for a cup of tea”, which is an infamous Chinese saying for being summoned to justify yourself in front of bureaucrats. Prof. Valeria Zanier, a historian and specialist in private economy and transitional media system in contemporary China who is also part of the sinology research unit at KU Leuven, was also contacted by The Voice and confirms the absence of self-censoring. In her opinion “this does not constitute a problem as long as I express my views in independent academic publications or conferences”. However, as explained in the French-language Belgian newspaper Le Soir, the CCP’s “long arm” is still perceived to be applying pressure on academia.

Nevertheless, Prof. Standaert does not think that assessing the involvement of the CCP in partner universities, analogous to the aforementioned China Defence Universities Tracker, would actually be helpful since the CCP is inevitable.

Every university or enterprise has party secretaries installed at all levels. Hence, according to Prof. Standaert “most of the important people you’ll meet during your trip to China and all of the people with whom you sign your contracts are members of the CCP.“ He added a second point, regarding the heterogeneity of the CCP: “Western laypeople often assume that the entire party is forced into the same line of thought even though differences exist and can be seen just by looking at how former President Hu Jintao has led China and how President Xi Jinping is governing. Hence, differences can also be seen at the local level. Also, in order to climb up the academic career ladder, you must join the CCP. Bluntly said, it is part of the survival mechanism.“ Prof. Standaert compared being part of the CCP to being part of the Catholic church, for the imagined case in which Chinese universities would like to assess “the involvement of the Catholic church” within KU Leuven.

What sort of measures should universities take?

When considering the complex problem of possible Chinese interference in academia, one can wonder whether there are other possibilities aside from avoiding working with Chinese scholars or shutting down institutions such as the Confucius Institutes? In response, Andreas Fulda proposes constraining the CCP by penalties for authoritarian aggressions. Moreover, he urges to refuse funding from foreign organisations with a poor human rights record. Meanwhile, according to an article by The Guardian the University of Oxford has chosen yet another option; students at Oxford specializing in the study of China are being asked to submit some papers anonymously.

The Voice also contacted Prof. Lut Lams, who focuses on Chinese media in the research group Multimodality, Interaction and Discourse at KUL, and asked what she would expect KUL to do. She responded that “I would want to make a plea for a case-by-case screening. Yet, I do want to emphasize that universities should not generalize and start to screen every student from a specific country. But special attention will have to go to security studies” When asked what she thinks about the accusation of xenophobia that some students made on the Pangaea community Facebook group, she said that she does not think this is a case of discrimination.

“When KUL says there is a danger of espionage, there must be something that they know but are not making public, and therefore I think they are acting reasonably. Yet, KUL will have to be more transparent about it. If there is a new policy, they will have to communicate that policy to their staff and students.”

Lut Lams, Professor at KUL's Multimodality, Interaction and Discourse research group

Conclusions & future outlook

The matter of academic cooperation with China is a delicate topic, with an opaque mixture of geo-politics, allegations, issues of security and ethics, as well as clashing academic norms. The debate suffers easily when arguments are oversimplified and the context is omitted. It shouldn’t be forgotten that China is a country of 1.4 billion people and the CCP is an elitist club of around 92 million members. Chinese students and scholars come here with their own motivations and dreams. Seeing a spy in every one of them creates an atmosphere of vicious paranoia. Sinophobia is already deeper engrained in our society than we’d like to admit as was recently exposed by Veto earlier this year in an article published during the first lockdown and then translated to English by The Voice. Therefore, the debate of whether or not to cooperate with other countries, particularly with countries that have been accused of attacks on human rights, and how to do so must be held without compromising our own integrity.

For more regular content

- Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thevoice.loko

- Check out our Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/thevoice.kuleuven/

- Listen to our podcasts on: https://www.mixcloud.com/The_Voice_KUL_Student_Radio

For submissions or applications

- Email us at thevoice@loko.be

- Or message us on Facebook