article> Leuven Life

Asian students in Leuven suffer consequences from anti-Asian stereotypes

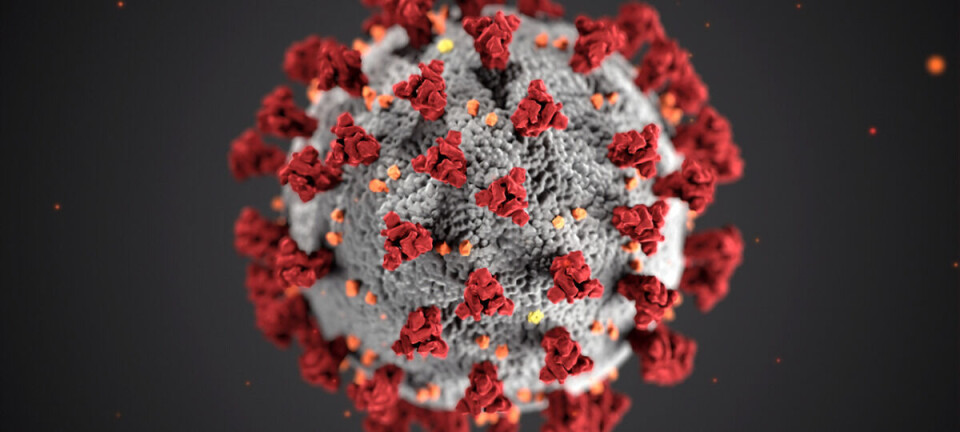

There is no escaping the coronavirus. The health crisis also has indirect victims as well. Asian students explain how because of the virus old and new stereotypes come to light.

Originally written in Dutch for Veto by Remo Verdickt & Maria-Laura Martens

Translated to English for The Voice by Remo Verdickt & Gwynne van Kaauwen (Contributing Writer)

Originally published on March 12, 2020

‘A child saw me walking down the street and ran away screaming.’ ‘I had just bought some hand sanitizer when a man started very aggressively yelling at me in front of the pharmacy.’ ‘During an online group project a fellow student kept insulting me and my country.’ These are just a few anecdotes from the nine testimonies Veto received after a call for Asian students to share their experiences.

Not an isolated incident

The recurring theme is that the fear of the coronavirus is being projected on the Asian community or laughed off at its expense. Students receive hurtful comments or worse, during both professional and daily life. Still, most try to put things into perspective. ‘I don’t expect any society to be perfect and this doesn’t affect my appreciation towards Belgians in general.’

Apart from the verbal violence, they also have to battle more subtle, unspoken misunderstandings and stereotypes about East-Asian cultures. The urban legend that the virus comes from bat soup is sufficiently known. This kind of misconceptions or exaggerations have lasted for centuries, and have evolved over time.

Stereotypes: old but evolving phenomenon

‘Voltaire & co looked up to China, a large unified country with one exam system. Europe could only dream of such.’

Nicolas Standaert, Research head of Sinology

Nicolas Standaert, head of the Research Group of Sinology at the KU Leuven, analyses and nuances: ‘Throughout history Europe has always had an interesting interaction between sinophilia and sinophobia. Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire looked up to China: a large unified country with one detailed exam system, at that time Europe could only dream of such.’

‘From the beginning of the 19th century this turned into a way more negative image, up to the anticommunist rage of the fifties. During the cultural revolution there was again a “China hype”, while now we look back at that period negatively. Just before the Olympic Games of 2008 there was another hype, but at this moment you can hardly find some positive comments about China.’

He also illustrates the complexity of “being Chinese”: ‘We talk about the stereotypes against people who look “Chinese”, but what does that actually mean? There are people of the first, second and third generation, international and national students, adopted or with parents of different ethnic backgrounds.’

‘The interesting thing about racial stereotypes is that purely on looks you cannot know to which group a person belongs and even if this person has a Chinese background, instead of for example a Japanese or Korean background. We project all our stereotypes on this,’ says Standaert.

A brief inquiry in the auditorium about discrimination confirmed his point. A student of mixed descent heard hurtful remarks at a restaurant. ‘She was immediately associated with Corona right away even though she is through and through Belgian. She has to learn Chinese just like all our other students.’

Face masks

Another clear sore point is the use of face masks. An anonymous Chinese student was ridiculed by a fellow student because of wearing one. She tried to start a dialogue about her reasons, but this was constantly laughed off. The student reported the incident at her faculty, but hadn’t received a response at the moment of writing this article.

Nan Lin, a Chinese student of anthropology, pointed out the cultural differences. ‘I heard stories of friends who tried to buy face masks and noticed how they were made fun of behind their backs. In Western cultures people only seem to wear them when they are severely sick, but in many East-Asian countries, also Japan and South-Korea, it’s almost an accessory or fashion statement (laughs).’

'Yesterday my mother sent me a message. She wanted me to come home, over there they tackle the virus better and it’s safer’

Nan Ling, student Anthropology

‘Of course we also wear it in some way for protection, and I don’t think people should point fingers at others just because they take precautions. Yesterday my mother texted me, worried, asking about the situation over here. She said that if needed I better come home, they tackle the virus better over there and it’s now safer (laughs),’ concludes Nan.

Hate crimes

The aggression is unfortunately not only verbal. A Somalian student told us he witnessed the physical intimidation of a Chinese friend two weeks ago. Three drunk Belgians approached the student in a ‘fakbar’ (faculty bar) in Leuven. The men made gestures to indicate that she should wear a face mask and then proceeded to brutally push her out of the bar.

Standaert sees stereotypes as a logical consequence of cultures interacting with affairs they’re not used to. The stereotype is not the problem, you just can’t act on it. ‘You laugh, and that isn’t a problem. I also state this in my lectures: “Keep laughing, because then you see the difference.” In a way, you discover it.’

The Somalian friend called the police and managed to take a picture of one of the offenders before they ran off.

Once on site, the police wrote a police report, specifically for a hate crime

Veto has no knowledge about any other reports like this so far. The Leuven Police could not provide any numbers of a possible increase in the amount of incidents during nightlife, because they were in an emergency meeting about the coronavirus at the moment of writing.

In any case, the legal consideration of these reports take time, while the international students often stay in Leuven for shorter periods.

Western media and framing

'People can find my personal concerns exaggerated, but political debates are not on the agenda’

Anonymous witness

Multiple witnesses lament the role of online misinformation. Nan Lin believes Belgians are too trustworthy when it comes to both social media and Western news agencies: ‘In China, all national media is controlled by the state. Because of this, Chinese people are suspicious of it and search for information in other sources as much as possible. In Belgium that suspicion is way smaller. While it is precisely the media who have been portraying China as the world’s biggest villain for the last few years.’

The anonymous witness to the face mask incident shares the same feeling. Her fellow student mixed his ridicules with criticism of China's internal politics, while referring to various online campaigns. This link between the virus and communism bothers her. ‘The actions of the Chinese government, shouldn’t be the core of this discussion. This crisis affects everybody. People can find my personal concerns exaggerated and I’m surely willing to start a discussion about that, but political debates are really not on the agenda.’

Being the bigger man

Remarkably, all witnesses emphasized they don’t feel any resentment towards the Belgian population. One man spoke about multiple indicidents on the street where he consistently avoided confrontation: ‘I felt like I had to be the bigger man.’

Also Weiyan Low, an anthropology student and Malaysian of Chinese descent, tries to put things in perspective: ‘It’s just about ignorant people. I don’t see it as a general hatred towards myself because I have a different skin color.’

As an anthropologist he also looks at the reactions of his Belgian friends. ‘When I talk about my experiences, many respond bewildered or very awkwardly. In a way it is comparable with how men deal with stories from female friends who have been harassed: when we don’t have experience with something ourselves, our solution to the problem is not necessarily the most rational.’

Just like Weiyan, Nan, a fellow student, realizes Belgians take Asian sensitivities less into account because the colonial relations are very different than with Congo, for instance. ‘A professor can joke about China, which he would never do about an African country due to the colonial history. People simply know less about our culture, and are therefore less thoughtful about their choice of words.’

Beyond introversion

One last stereotype that can by now be put to rest: Chinese people lead a withdrawn life, very much keeping to themselves. All witnesses who contributed to this article were extraordinarily friendly and open. Nan laughs when about about the prejudice. ‘Most Chinese students here are engineers. In the Social Sciences there are a lot less of us, but these people are definitely more socially active. You know, in China we also have our own stereotypes about introverted engineers (laughs).’